Tresacare Featured in New Theos Report 'Love's Labours'

- Krystle Wong

- May 14, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: May 21, 2024

We are so glad that care work is getting the attention and advocacy it deserves through Theos' new report – and that we get to be a part of it.

We’re excited to share that Tresacare has been featured as a case study in the latest Theos report as part of their Work Shift: How Love Could Change Work research series. The latest and third report is called Love's Labours and it is dedicated to the unseen challenges of social care work. Love's Labours was launched on April 26th and is now available to download.

As you can imagine, we're delighted to be featured in such meaningful social research whose mission resonates so strongly with ours. Care work demands mental and emotional labour, a cost that does not get factored into the job description, wages or working conditions. Care workers are asked to give so much and so regularly, that often they are giving out of an empty cup. This is why burnout remains the leading cause for care workers to leave the industry.

Love isn't a typical subject matter for social or economic research, but in this latest report Love's Labours, senior researcher Hannah Rich invites us to examine and unpack our understanding of labour – and what it would mean for individual workers and society if we were to factor love into the valuation of labour.

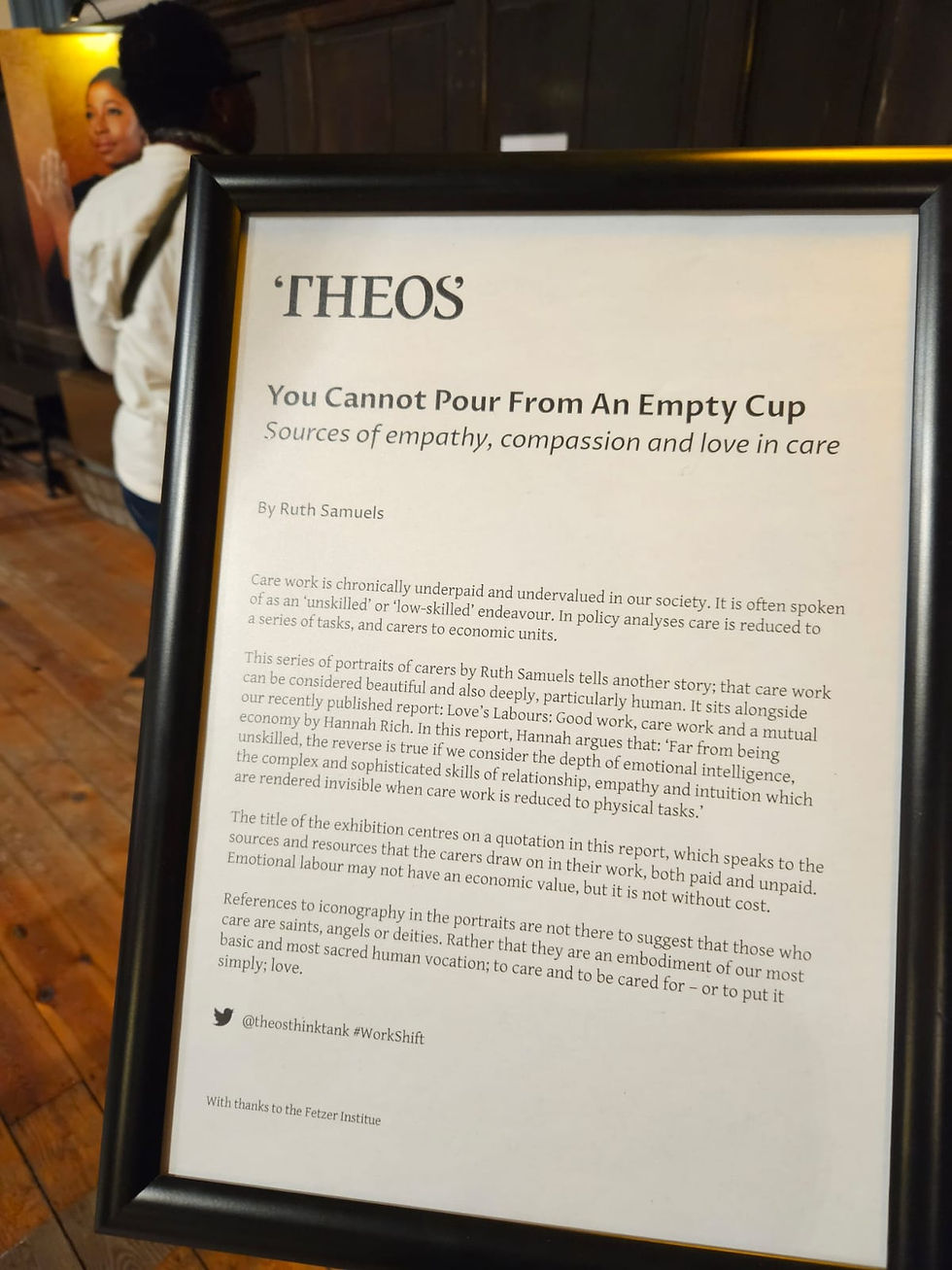

'You Cannot Pour From An Empty Cup' Photography Exhibition

At Tresacare, we often point out in training that "you cannot pour from an empty cup". This imagery resonates very strongly with care workers, and it got picked up as the title of Ruth Samuels' photography exhibition at the launch event for Love's Labours. Commissioned by Theos, Ruth created a series of portraits of care workers that depict them the way they deserve to be perceived: with love, dignity and appreciation.

What's the Work Shift Series About?

Most of us have been conditioned to think of work and labour in economic and financial dimensions. But think-tank Theos is using their three-part Work Shift series to spotlight the troubling nature of certain modern working trends and to shift our understanding of work.

They take an unusual approach by focusing on the relational rather than economic aspects of work. Work is more than just a source of income; it’s a way we connect with others and contribute to our communities. Theos encourages a shift from the traditional focus on productivity and profits to a more holistic view of work’s impact on individuals and society.

The first report is called Ties That Bind and spotlights the rise of lone working and insecure work in the UK. Although many enjoy the flexibility of remote work, we have not yet begun to appreciate the effects of isolation on solidarity, mutuality, relationships and health. The second report is called Working Nine-to-Five and addresses how we have fallen out of love with work.

The third and latest report Love's Labours – in which Tresacare features as a case study in the final chapter – explores the unseen costs of social care work, where love is arguably the key skill needed in the call to care. In this report, theology and economic inequality expert Hannah Rich takes into account the unpaid aspects of emotional labour that comes with caregiving, and suggests it is time to reframe how professional care workers should be valued.

Here are a couple of thought-provoking excerpts that remind us of the humble origins of welfare and care work, and how we still have a long way to go in terms of recognising social care work as valuable, high-skilled work:

Framing something as love is often what allows it to be undervalued or unpaid. It is, as we have seen, easy to forget the role of love within care work and to focus too much on the economic conditions of work. There is a shadow side to this idea, however, which risks pivoting too far in the opposite direction and ignoring that care work, both paid and unpaid, is still work.

Decades ago, the welfare system was designed on the premise that care would be largely unpaid, domestic, women’s work. Over time, this shifted and came to be understood instead as a function of the state. Now, these structures are fraying to the point where it is once again unpaid, undervalued, predominantly female carers who are filling the gaps out of necessity and desperation rather than choice. Alongside this, people are living longer with complex needs, more of us – women in particular – are balancing paid employment with unpaid work responsibilities, and a greater proportion of the population are ageing without children. We have come full circle, it seems, yet the pressures are even greater than they were half a century ago.

It was an honour to be asked to share our Tresacare insights with Hannah, the author of Love's Labours, and to be a part of Theos' meaningful social research project. We are so glad that social care work is getting the attention and advocacy it deserves through Theos' efforts.

Comments